Being an active reviewer

Being a reviewer

At our DCEA seminar in August we had a discussion abut reviewing scientific papers. The discussion was basically about how many papers one should review. So it was a sort of ethical discussion about peer review as a component of the researcher’s job. Due to lack of time we didn’t conclude the discussion and this left me quite unsatisfied. Reflecting upon it, I realised that I know in fact very little about how active are my peers as reviewers, and how I compare to them in this sense. Am I reviewing too many papers? Too little? Am I receiving too many review invitations? Too little? I decided to find out.

The active reviewer survey design

I could have done some literature review and found the answer to my questions. But why not getting primary data instead? More fun. So I designed an anonymous mini questionnaire with 5 simple questions. I asked for the number of reviewer invitations you get, how many of these you are qualified to review, how many papers do you actually review, and how many do you think you should review. Then I left an open field comment to elaborate on the answers. Then I checked about opinions on reviewing papers based on the points raised during our earlier group discussion (e.g. is it a waste or time? Is it intellectually stimulating?). A couple of categorial variables on affiliation and scientific background - because I expected the number of reviews to different between academics, non academics, and natural, social, formal scientists, and I didn’t know who was going to answer - and that was it. After testing it on my colleagues at DCEA and revising based on their good comments (e.g. adding the comment box, thanks qualitative people), I distributed it on LinkedIn, Twitter, and via mail.

I do the reviews I wish to do

Here the main highlights from the survey. If you are curious for more details, you can download the survey raw data and the R code for the data analysis.

I got 60 respondents, down to 57 after removing inconsistent answers (stating more reviews done than invitations received, or no invitations received). Affiliation: 48 Academia, 9 Outside academia. Background: 37 Natural Sciences, 15 Social Sciences, 5 Formal Sciences (definitions here).

Let’s have a look at the results:

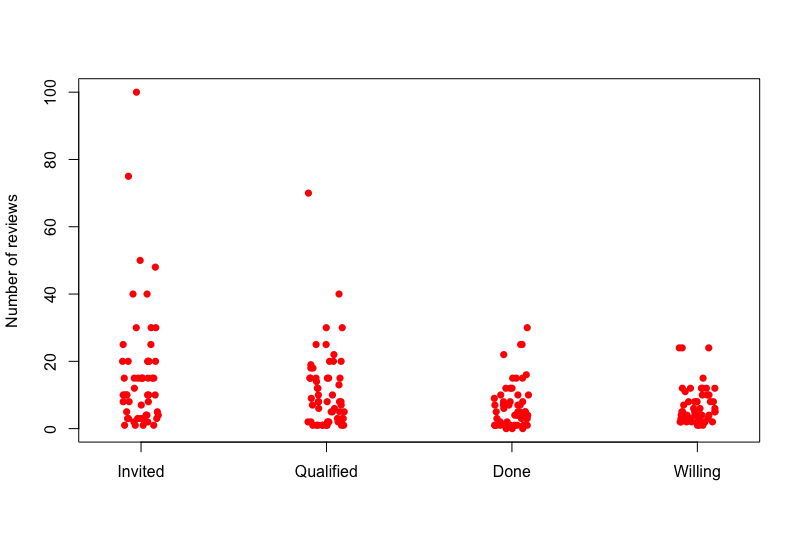

As expected, the respondents received invitations that they were not qualified to review (approx. 6 qualified invitations out of 10 received). Even if qualified for the job, respondents didn’t always accept invitations (approx. 6-7 done out of 10 qualifying). Finally, the number of reviews done by the respondents was generally similar to the number of reviews they think is appropriate to do (approx. 1 to 1 relationship).

There are of course differences by scientific field. I knew I had some cryptographers in my network and they are super-active reviewers in general, things work a bit differently in their field, so I am not surprised by the high scores for Formal Sciences. Social scientists seem the less active, but I have a lower number of respondents so it might be just an impression (I haven’t tested statistically because…I am lazy).

Here the mean and (standard deviation) of the number of reviews per year per scientific group :

| Invited | Qualified | Done | Willing | |

| Natural | 16.64 (4.08) | 12.27 (3.50) | 6.91 (2.63) | 7.05 (2.65) |

| Social | 11.20 (3.34) | 6.00 (2.44) | 3.80 (1.94) | 4.18 (2.03) |

| Formal | 29.60 (5.44) | 19.80 (4.44) | 13.60 (3.68) | 10.8 (3.28) |

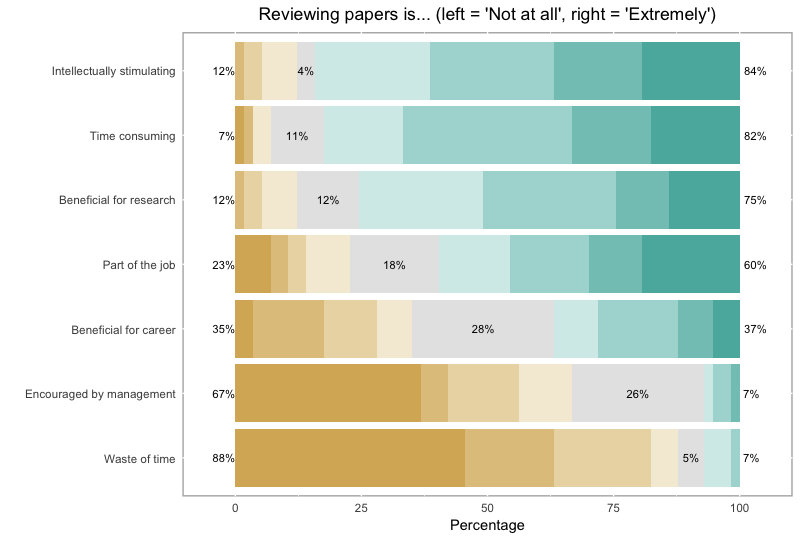

What are the opinions of the respondents about reviewing papers? Let’s see.

Seems like reviewing papers is definitely intellectually stimulating. Even if it is considered a time consuming task, it is not perceived as a waste of time, and instead considered beneficial for research. The funny thing is that although it is perceived as part of the job, it is not encouraged by the management according to the respondents…! I think respondents are a bit undecided on how beneficial is reviewing papers career-wise.

At a quick testing, these variables seem poorly correlated. This may be a good sign. It may signify that the variables addressed different and non-overlapping issues and their selection was thus appropriate. The main highlights are the moderate correlation between benefit for research and for career and the moderate inverse correlation between being intellectually stimulating and being a waste of time. Both make sense considered that the respondents are mostly academics (their career is in research, they value intellectual work).

The comments

The qualitative comments are really instructive and interesting. You can check all of them in the raw data. Here some excerpts:

“I author/co-author in average 3-4 papers per year, each should have at least 3 reviewers. So for each paper I submit I should review 2-3 papers.”

There is more than one respondent that follows this line of thought. Their activity as reviewer is directly proportional to their activity as authors, and slightly higher.

“Two a month seems reasonable” “Around one per month” “Once in two months” “One review per month”

Etc. Pick your favourite. This is the second group of respondents. Those who quantify their reviewer activity primarily based on the time available, because reviewing papers takes time.

“Every researcher with enough experience to peer-review papers should make this effort regularly and honestly”

“Reviewers should be compensated by publishing companies”

“It is a task which is part of the academic life but not of the highest priority”

The ethical, the utilitarian, the pragmatic. The diversity of opinions.

Lesson learnt #1. Benchmarking

I didn’t take the survey myself. But I am happy I did this little exercise because I learned a lot. I can see that my scores are in the high end of the distribution (both in the case of being a Social scientists and a Natural scientists). I receive about 50 invitations per year and are qualified to carry out half of them. I review around 8 papers per year, and I think I could do a bit more. I also think I should review a bit more than I publish (2:1 ratio as a rule of thumb) depending on the time available (at least one review per month is realistic).

Lesson learnt #2. Survey distribution

I had a hard time getting respondents. Initially, things went wrong due to technical issues. Even after fixing the technical problem, I could observe that while my LinkedIn post was being seen by hundreds of people, nobody was clicking on the survey link. Nevermind Twitter, too little followers there. Two days before survey closure I decided to use my secret weapon: a mailing list I put together just for this survey. I got 30 responses in 2 hours. This confirmed what I read somewhere some time ago that mailing lists are the best way to get survey respondents.

Lesson learnt #3. Collateral benefits

Thanks to this experiment I got some new friends on Twitter and thanks to one of them I discovered Publons.

I've had a good experience so far with @Publons. The more people that join, the better picture of the peer-review community we get https://t.co/7W8oZz8YkN

— Moana Simas (@moanasimas) October 17, 2017

That’s really a great project, I think. I signed up immediately and after some days they had confirmed all my reviews and I had an updated profile. Now I can also document my activity as a reviewer e.g. in project applications. See my updated reviewer stats, for example.

Acknowledgements

One important thing to conclude: thanks to all the survey respondents and to those who helped distributing the questionnaire. Your feedback was really much appreciated. Hope the results will be useful for you as they were for me.

UPDATE September 2018: there has just been a large study published on this topic by Publons. Access the report here or check the related Nature paper here for summary stats, which are really interesting. In particular they touch on the topic of differences between developed and emerging economies and the apparent “review fatigue” where editors must invite more reviewers to get the job done.